If the loss of Opportunity the Mars Rover demonstrated anything, it is that human beings have a great capacity to form weird attachments to stuff that shouldn’t elicit our pity. The poetic translation of Oppy’s last words—“My battery is low and it’s getting dark”—had me ready to abandon writing in favour of aerospace engineering. Someone needs to bring that brave robot home. It will be lonely and cold out there!

But really, that’s just scratching the surface when it comes to the ridiculous ways in which human empathy manifests. Given a compelling narrative, we can find ourselves caring for just about anything.

I struggle to eat chocolate Easter bunnies. I am aware that this is ludicrous, but there is a very small and very stupid part of my brain that shrinks from biting off their ears. Because… poor bunny.

And matters can grow murkier still when the object of our sympathy is not a chocolate rabbit or a stoic robot. Do we still feel sorry for a long-suffering-but-far-less-innocent individual, for the perpetrators of atrocities, the devourers of worlds, and the shadows beneath the bed? Often, yes. Should we? That’s harder to answer, but authors persist in asking the question.

Maybe they’re malicious. Maybe they’re helpless victims of their own nature. Maybe they just think we are the tasty bunnies. Here are five books featuring monsters that we might still pity as they bite off our ears.

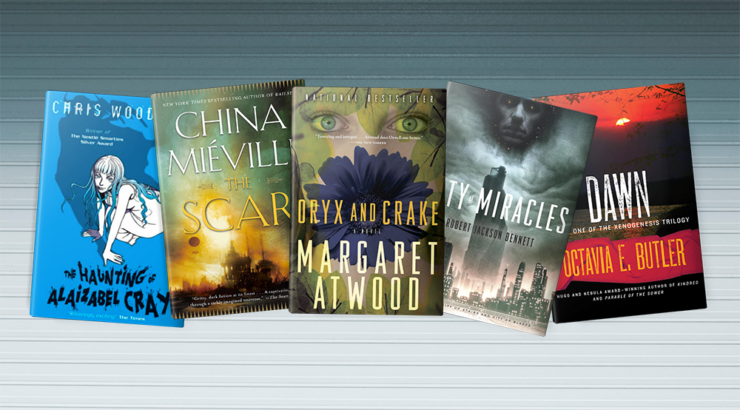

The Scar by China Miéville

To be honest, this list could easily be filled with Miéville monstrosities alone. From the contents of the ‘Säcken’ in the short story of the same name, to Yagharek in Perdido Street Station, to the whole menagerie of macabre Remade in the Bas-Lag Trilogy, pitiable and grotesque monsters proliferate in his work. And in The Scar there are the Anophelii.

The Anophelii, or mosquito-people, rose to power as a dominant race during the years of the Malarial Queendom. While their reign of terror was short-lived, the devastation they wrought resulted in their entire species being banished to a small island for the next 2000 years.

Male Anophelii are mute vegetarian scholars. Female Anophelii are ferociously hungry predators with retractable, foot-long proboscises inside their mouths, capable of draining all the blood from their victims within a minute and a half. Everyone is, quite rightly, terrified of them.

And yet, although the mosquito women spend most of their lives starved and blood-crazed, they experience a brief window of lucidity after feeding. Stabbing proboscis aside, their mouths are more similar to a human’s than to males of their own species. But when they attempt to reach out to other people, to communicate, they are immediately met with fear and violence.

Buy the Book

The Scar

City of Miracles by Robert Jackson Bennett

The antagonist of the final volume of Bennett’s Divine Cities Trilogy meets Sigrud while the latter is busy conducting a delicate conversation with a man in a deserted slaughterhouse. When the man reveals the name of his employer—‘Nokov’—the lamps in the building flicker out one by one, until Sigrud stands in the last remaining pool of light.

Nokov, a kind of demigod of darkness, can move through the shadows anywhere on the Continent. Say his name and he will appear. While he is terrible and primal and powerful, on some level he is also a teenager who has grown up in a world that has sought to use and harm him.

The most tragic aspect of Nokov is that his cruelty and violence never feel inevitable; the possibility of his redemption dangles just out of reach. There is the pervasive sense that maybe all he really needed was a hug from his mom.

Buy the Book

City of Miracles

Dawn by Octavia Butler

Lilith Iyapo wakes in a dim room every day, but it is not always the same dim room. Bathrooms appear, disappear, sometimes there is furniture and sometimes not. After the war that wiped out the greater part of humanity, she found herself kidnapped by the Oankali alien race and imprisoned on their spaceship for 250 years. Intermittently, the aliens question her and put her through tests.

Unlike the other books on this list, the monsters in Dawn are ostentatiously benevolent, if very disturbing in appearance. They are trying their best to save humanity and forge non-hierarchical communities to prevent humans from obliterating themselves in the future. However their methods of reforming our behaviour are very much focussed on the greater good, rather than a test subject’s individual wellbeing—and whether we consent to the grand experiment is entirely immaterial.

Buy the Book

Dawn

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray by Chris Wooding

Twelve-year-old me was delighted by the selection of monsters on offer in this gothic steampunk horror, which ran the full gamut from cradlejacks and body-stealing spirits, to the devilish Rawhead and Bloodybones (“Rawhead close behind you treads, three looks back and you’ll be dead”). A scene involving the Draug – or Drowned Folk—was the first instance in which I can recall feeling properly frightened while reading.

However the monster that lingered with me the longest happens to also be the most human. Stitch-Face, a serial killer stalking the streets of London, is aggrieved to discover that someone has been copying his work. In addition, that someone seems hell-bent on destroying the city and everyone in it.

In conversation with Alaizabel, Stitch-Face acknowledges that he is a monster. But, in his own words, “even monsters want to live.”

This admission did not make him sympathetic or less frightening, but it did have a kind of logic that was almost relatable.

Buy the Book

The Haunting of Alaizabel Cray

Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood

Pigoons. Hybrid animals designed and grown as foolproof organ donors by OrganInc Farms. A pigoon is created by splicing human genes into pigs, which has the side-effect of greatly improving their intelligence. In order to accommodate the extra organs, they’re also much larger and fatter than their unmodified cousins.

In the early chapters of the Oryx and Crake, six-year-old Jimmy expresses sympathy for the pigoons and sings to the animals from a safe distance. He particularly likes the little pigoonlets. But when he encounters the escaped animals as an adult, they aren’t quite as endearing, especially after they start applying human intelligence in their efforts to hunt him down.

Buy the Book

Oryx and Crake

Is there something uncomfortable in our love of monsters, in the way we so readily absolve them of their sins at the expense of their victims? I grappled with this question while writing The Border Keeper. To be honest, I don’t think I ever fully arrived at an answer. Latent humanity lies in the shadow of any good monster; perhaps it speaks well of us that we can empathize with them despite their transgressions. Or maybe, beyond the tentacles and teeth, they are not so different from us.

What are you willing to forgive?

Kerstin Hall is a writer and editor based in Cape Town, South Africa. She completed her undergraduate studies in journalism at Rhodes University and, as a Mandela Rhodes Scholar, continued with a Masters degree at the University of Cape Town. Her short fiction has appeared in Strange Horizons, and she is a first reader for Beneath Ceaseless Skies. She also enjoys photography and is inspired by the landscapes of South Africa and Namibia. The Border Keeper publishes July 16th with Tor.com Publishing.

Kerstin Hall is a writer and editor based in Cape Town, South Africa. She completed her undergraduate studies in journalism at Rhodes University and, as a Mandela Rhodes Scholar, continued with a Masters degree at the University of Cape Town. Her short fiction has appeared in Strange Horizons, and she is a first reader for Beneath Ceaseless Skies. She also enjoys photography and is inspired by the landscapes of South Africa and Namibia. The Border Keeper publishes July 16th with Tor.com Publishing.

I’m thinking that John Gardner’s Grendel is one of the best examples of this trope.

Just want to get this in, before the howls of “HOW COULD YOU LEAVE OUT [my favorite example]”

The title is FIVE books, not ALL the books.

Just sayin’ :D

Regards,

zdrakec

“I struggle to eat chocolate Easter bunnies. I am aware that this is ludicrous, but there is a very small and very stupid part of my brain that shrinks from biting off their ears. Because… poor bunny.”

Hit the legs first. Then the ears won’t seem so terrible.

I’m absolutely certain that this is not Butler’s intent, but when I read Dawn it was immediately clear to me that the Oankali had wiped out humanity (possibly by using their superior tech to start the war), and then lied to the survivors to make them more cooperative.

@1

I read Grendel when I was 12, on a librarian’s recommendation. Apparently it was marked as “fantasy”, and I liked “The Hobbit”, which was also marked as “fantasy”, so…

Octavia Butler’s work has a lot of rape in it, dressed up as “saving humanity”. Just because its an alien doesn’t mean its not rape.

The Oankali, by their own admission, have absorbed a lot of different species. I’m sure they told each how they were saving them from themselves.

@5. Oh, dear. I’m reminded of the poor youngsters who watched the animated ‘Watership Down’ because it was a cartoon about bunnies.

we had to read <i>Grendel</I> in junior year of high school, after we had already read <i>Beowulf</i>.

Great list, definitely picking up some suggestions

@5: ouch.

Re: the Oankali. it is explicitly stated in the book that the Oankali do not usually ‘trade’ with other species (they see the act as commerce, and Oankali means something close to ‘merchant’ in their own language) without the species’ consent. They made an exception with humanity because the nuclear war that had started before their arrival was well in its way to eradicate the whole species, and they saw our genetical propensity for cancer as too valuable a trait to let it go to waste. And they did it not without second thoughts and very heated arguments; in fact, the skepticism of part of the Oankali society about the whole endeavour is a constant theme resurfacing again and again throughout the whole series.

@3 — No, legs first is just cruel. Biting the head off immediately is the only way to be kind to the bunny while still eating the delicious chocolate.

@6, @7

If I remember, it was always a bit of an unasked question as to whether the Oankali caused the apocalypse the preceded the trilogy’s setting.

@atlas, #10: that’s what the Oankali say to the humans and part-humans. I, as a naive reader back shortly after publication date, never even considered the possibility that they were anything but lying genocides who had caused the disaster. For one reason, the timing was too darn convenient, their discovering humanity just as we obliterated over 99% of ourselves.

@8 @10

Fortunately a lot of Grendel went right over my 12 year old head so I wasn’t unduly traumatized. My reaction was mostly “What the heck is this?” coupled with “eeeww” in parts. It certainly was interesting. I understood it a lot better when I was in high school. “The Forgotten Beasts of Eld” was in that library and I read it around that time.

I was also 12 (in 1977) when I first read “Dune” which was a little less inappropriate for a 12 year old. I was somewhere in high school and rereading it for maybe the 4th or 5th time when I realized that the Baron was gay, and wanted to rape Paul.

I don’t think that the library had a separate “YA” SFF section, so anything more adult than Narnia was in the adult section.

Dawn looks a bit interesting, wish there was a little more preview

@16 Octavia Butler’s works have profoundly changed my view of the world and society. I can’t think of an author that has touched me more. Dawn would definitely be in my top 10 list of all fiction. Consider reading the other two books in the Xenogenesis Trilogy (and everything else she has written).

Whoever wrote the description for Oryx and Crake….did they even read the whole book or just skimmed a few pages about the pigoons to meet a deadline? Oryx and Crake belongs in this list but not for the pigoons. The book is incredible but your description does not do it justice nor accurately portray the true monster.

@Drew

That would be me. Yes, I have read the whole book or I wouldn’t have included it. I feel pigoons are both immensely sympathetic and also frightening. Thus, in my view, they fit my criteria for this list as set out in the introduction.

That does not, however, preclude other monsters from existing in the same work.

I would have thought that the terrible monster tugging at the heartstrings from The Scar would be the Avanc. Trapped outside of its home dimension and forced into labor on behalf of Armada? Awful stuff.

Tor keeps extending my want-to-read list beyond endurable limits.

I did read Dawn though, and I’m on a long overdue and still sporadic mission to read everything by Octavia Butler. The last chunk being the Patternist books.

Tip: You don’t have to like the Oankali. For that matter, you don’t really have to like people either. Or sharks, bats, giraffes, roses, mushrooms, beetles … they are what they are.

And what they are is – interesting.